It has been a year since Santa Monica College began “climatizing the curriculum.” The term refers to a push—supported by the Blue Economy & Climate Action Pathways (BECAP) program—to spread climate-related readings, case studies, problem sets and project assignments across the syllabi of every academic department.

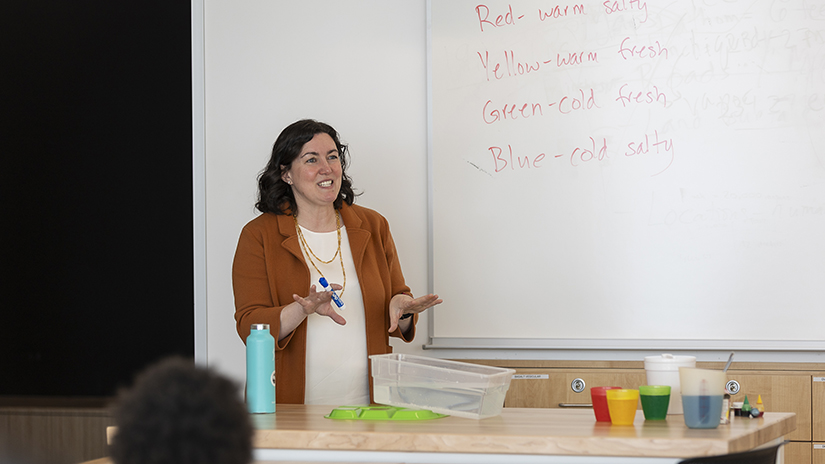

But there was, until now, just one course in the SMC catalogue devoted exclusively to climate change: Geology 3, “Weather and Climate.” That changed this semester with the rollout of Geology 9, “Climate Change.” SMC’s second entirely climate-focused course is the brainchild of Lisa Collins, a professor of geology in the Earth Science Department. More than six years went into developing the course and shepherding it through the approval process.

Lisa’s deep dive into climate change reaches back to geologic time—long before the Industrial Revolution ushered in mass extraction of fossil fuels, railways, the internal combustion engine and the proliferation of greenhouse gases.

Her students first learn how tectonic-scale events have shaped Earth’s climate across eons. She explains how oceans and the atmosphere work together to regulate climate and weather, and how changes in both have influenced global environments and organisms. Only then does she delve into the impacts of modern human activity and how today’s policy decisions will shape future emission scenarios.

“I have taught elements of this class in other contexts,” she says—citing advanced courses in oceanography and paleoclimatology at her alma mater, USC—“but we never had time to talk about policy and politics. With this course, I tried to take the best parts from each of those.”

What is geologic time? How do tree rings and isotopes operate as yardsticks in climate history? What controls ocean circulation?

Marcos Jimenez is finding out. A first-year undecided major leaning toward business and marketing, he enrolled in Lisa’s class to meet the IGETC area 5A physical science non-lab GE requirement. He admits to initially feeling intimidated by the hard-science hurdles, but he quickly overcame his misgivings.

“I really like the way my professor lays out the course—one topic each week,” Marcos says. “Yes, there’s a lot of science, a lot of chemistry, but she has a great way of explaining things to people with no science background. She makes the material understandable, using charts and visuals, and goes into a lot of detail.”

A 22-year-old native Angeleno who lives in North Hollywood, Marcos has found it “really eye-opening to learn how rain is created and how deserts are formed. I never knew how complex climate is or how many small things play a role,” he says.

“What really fascinates me,” he adds, “is how important the ocean is to climate, and how our impact on greenhouse gases plays a huge role in climate change. I hadn’t realized these things before.”

Such words are music to Lisa’s ears.

*

Originally from Boston, Lisa spent her teens on the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. Her dad was a mail handler and union leader who moved the family to the Washington, D.C. area when Lisa was in middle school. She attended University of Maryland at College Park, where a series of GE courses turned her on to geology.

“It’s such a broad field. You learn a little bit about everything,” Lisa says.

An extremely rewarding internship at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and a life-altering oceanographic research voyage to Brazil led Lisa to a doctoral program in biogeochemical oceanography at USC. After completing her PhD in 2009, she stayed on as an instructor and later as director of the USC Environmental Studies undergraduate program. Since 2016, Lisa has been a professor of geology at SMC.

She and husband Dorab Sethna, a biomedical device engineer specializing in patient safety for MRI manufacturer Abbott, live in Culver City with their three children Ari, 12, Avi, 8, and Ayla, 2.

What spurred Lisa to create Geology 9 was a desire to connect the scientific information and policy questions at the heart of climate change debates.

“Let’s talk about politics,” she says. “Let’s talk about pollution. Let’s talk about international environmental agreements.” Those topics are not covered even in Geography 3, she notes.

Earth Sciences department chair Eric Minzenberg backed the idea, having previously seen Lisa launch Geology 32, the 4-unit physical oceanography course with a lab component. She has previously, as a Drescher Chair of Earth Science grant awardee, led that class on many field excursions to the Channel Islands. And funded by that same grant, in collaboration with the SMC Sustainability Center, she teamed up with Ferris Kawar to add Santa Monica College to the global network of 35,000 PurpleAir monitors continually tracking particulate matter in the air.

She currently collaborates with partners at USC, Caltech and Cal State Fullerton on California SeaGrant-funded research that places SMC student interns in their labs studying the presence and movement of DDT and its breakdown products in the sediments of the San Pedro Basin.

*

This semester, Geology 9 (crosslisted as Geography 9) made its debut in an asynchronous online format. To Lisa’s delight, the 45-seat capacity was filled before she even got around to promoting it.

So far, she reports receiving only positive feedback. Mindful that eco-depression is a real concern, Lisa keeps “doom and gloom” out of her lectures, emphasizing positive research findings as much as possible.

“We can’t just beat our students over the head with: ‘The sky is falling, the world is ending,’” she says. “I have three kids. My last kid was born just two years ago. I wouldn’t have had another child if I didn’t feel some optimism for my future.”

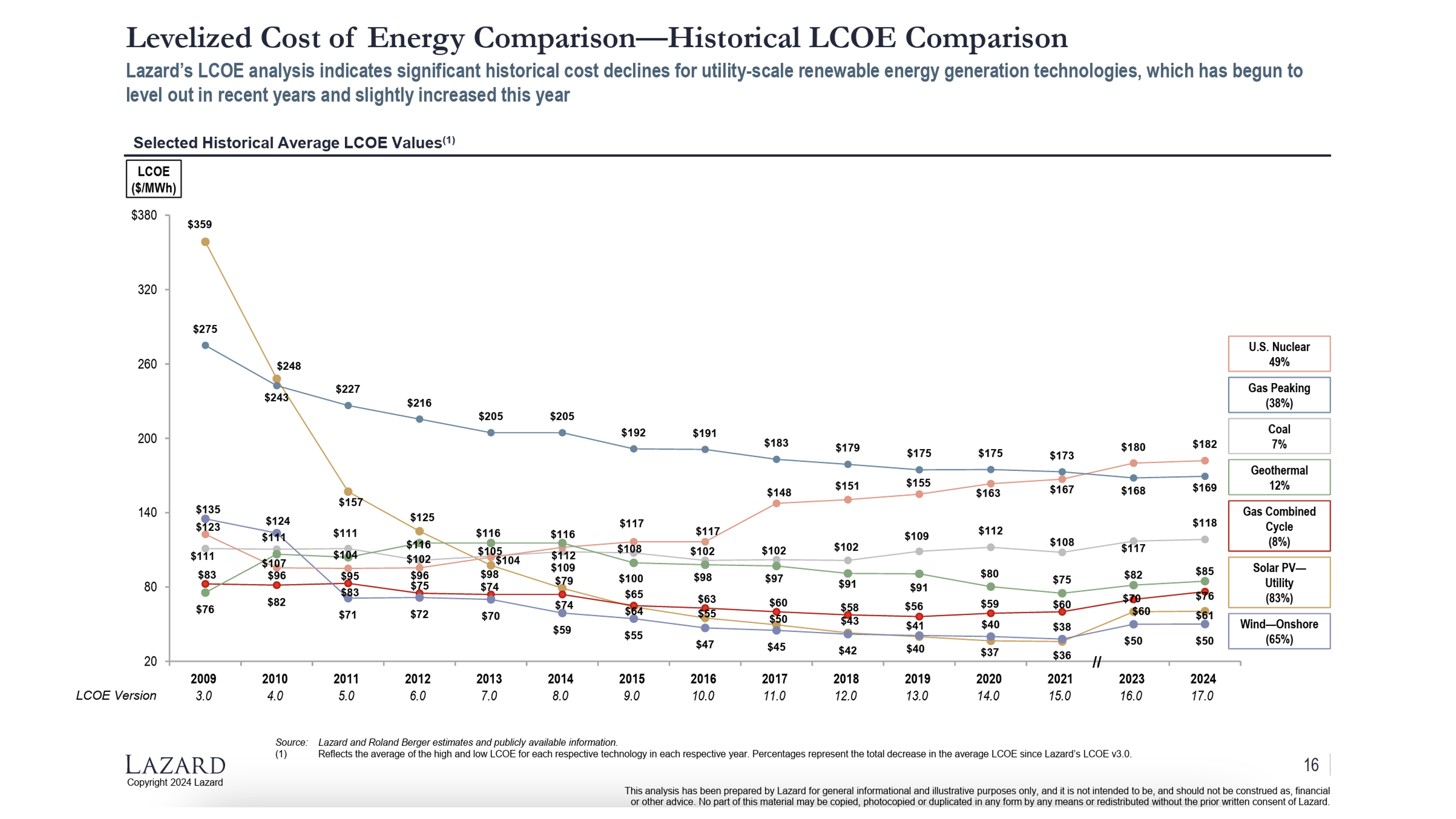

Lisa’s favorite data set comes from the latest Lazard LCOE report. “Levelized cost of electricity” (LCOE) is a metric for tracking the cost of electricity over the lifetime of a power plant. A graph found on page 16 of the 2024 report shows that wind and solar—without subsidies—have been competitive and sometimes even less costly than fossil-fuel power plants since 2016.

“I always love showing students that graph,” she says, smiling.

Another reason for optimism: The process for permitting and building a wind power plant in the U.S. now takes less than a year, while a coal-fired power plant takes 10 years.

And while China and India are still burning copious amounts of coal, Lisa believes they’re poised to leapfrog the West. Developing countries, she explains, “don’t have to go through the phases of coal-fired and gas-fired power plants. They could just skip right over into solar and wind.”

Sustainable energy comes with its own “trade-offs,” she acknowledges. Off-shore wind turbines are prone to rust, and solar farms in the desert encroach on the habitat of endangered tortoises.

“So we have to have those hard conversations,” she says.

Students in her Geology 9 course have been engaging in such conversations during Earth Month in modules focused on alternative energy.

Her hope is that they’ll come away from the course “understanding the basics of how climate works and what forces control climate change, how policy and politics have influenced where we are today, and what the future might hold.”

Also important, she believes, is to show students “that they have agency, they can make choices that are better for the climate, can take the lessons from class back home, can tell their mom or a friend.”

“If ideas from the course stick in their heads, then my job is done,” she says. “I think that’s what I’m meant to do.”

* * *