As a child, Maria Hernandez couldn’t understand why she wasn’t allowed to travel with her classmates to other

states for school programs. When she was in seventh grade, her mom and dad gently

broke the news: She was undocumented. Her younger brother and sister qualified as

citizens because they were born in the United States. But Maria was born in El Salvador, and her parents moved with her to the U.S. when she was just one and a half.

“I didn’t understand why my not being born here was a problem — or why it limits so

many opportunities,” she says. Not only is she denied a work permit, but travel restrictions

prevent her from visiting her great-grandmother and other relatives in El Salvador.

“I FaceTime with them sometimes, which helps,” she says.

The family originally journeyed to the U.S. for medical reasons. “We came here because

of me,” Maria says. As a baby she suffered from severe seizures after contracting

a rotavirus, and the physicians in her native country were unable to help. “My parents

came here for my health and for better opportunities,” she adds.

The U.S. government may have limited those opportunities, but Maria still seizes as

many as she can. This includes being the first member of her immediate family to attend

college. Wanting to repay the privilege of receiving healthcare here, she is studying

at Santa Monica College to become a nurse. Students completing SMC’s accredited nursing program are eligible

to take the national licensing exam for becoming a registered nurse. The curriculum

also prepares students to transfer to Bachelor of Science programs and further expand

their professional horizons.

So as soon as this nation allows her to pursue her career, Maria will be ready.

Found in Translation

After toying with notions of becoming a zookeeper or firefighter, Maria felt drawn

to the medical profession by the time she reached middle school. Already fascinated

by science, she says, “whenever I had to go to the emergency room or a medical appointment,

I always paid attention to what the doctors were doing.”

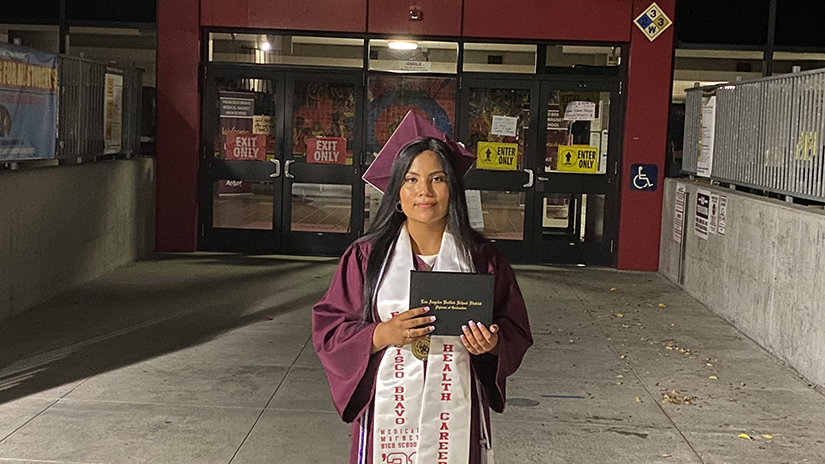

Soon she was accepted into Los Angeles’ prestigious Francisco Bravo Medical Magnet High School. But the nursing profession began to hold more attraction than becoming a physician.

“I noticed that whenever I went to the hospital, I’d spend more time with nurses than

with my doctor,” she recalls.

Calling herself a “people person,” Maria also realized the importance of interpersonal

skills to being a nurse. “I want to spend more time communicating with patients and

their families than doctors are able to do,” she says.

She also plans to draw on her Spanish-language skills, which she initially honed by translating for her mom and dad. The

shortage of Spanish-speaking nurses and physicians, Maria notes, causes too many Latinos

to avoid necessary care because of their discomfort with language barriers. To help

overcome the obstacles caused by this lack of representation, she says, “I want to

give back to my community — especially the Hispanic community — so people can see

more faces like mine in the field of nursing.”

Finding Support

Maria’s SMC studies began during the COVID-19 pandemic, when safety measures had forced

all courses online. Preferring in-person contact, she admits to struggling during

her first semester. “But I stayed positive, and the professors were all really patient

and supportive,” Maria says. She was especially grateful to Professor of Chemistry

Roman Ferede for making sure nothing was lost while instilling laboratory skills through a computer

screen.

Still, Maria didn’t feel like she was getting the true SMC experience until all students

and faculty returned to campus. “Now I see how diverse the college is,” she says.

“And I’ve been able to connect with people who are undocumented like me, so that makes

me feel welcome.”

SMC’s DREAM Program is part of that welcoming environment, according to Maria. The program offers a range

of support services for undocumented students — from academic, career and personal

counseling to workshops and assistance in applying for financial aid.

Healthy Future

Maria applied to the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, hoping to be accepted as a DREAMer herself. Having run on the cross-country team at Bravo High School, she knows all about the

commitment needed to finish a marathon, and the arduous path of gaining DACA status

is certainly that. In addition, she has practiced Shotokan karate for five years and will earn her black belt soon.

“I’ve always liked sports having to do with self-defense,” she says. Like cross-country,

Shotokan also demands endurance and stamina — ideal qualities for success in her future

nursing career as well as for weathering the bureaucratic limbo in which she currently

finds herself. So even though political forces currently stop her from obtaining a

work permit, Maria remains optimistic about the future.

“I have learned to be patient,” she says. “My time will come.”

* * *