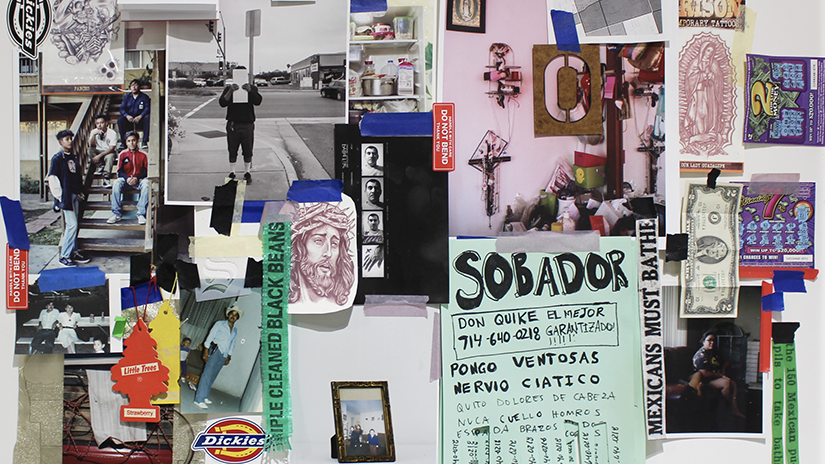

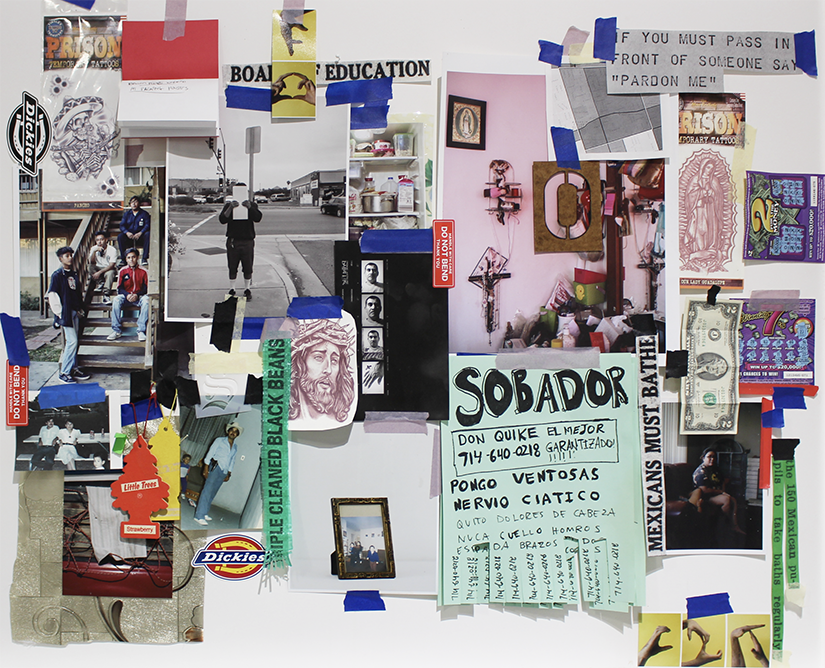

It is no exaggeration to say that Alkaid Ramirez embodies the art of washing machine repair.

In an installation titled “Hernecia Laboral” (labor inheritance), this Anaheim-based Chicano/x artist dons a blindfold imprinted with his father’s enlarged eyes. Screw-driver in hand, Alkaid proceeds to sightlessly disassemble a washing machine in minutes. The exposed washer drum becomes Alkaid’s media, on which archival family photos and video are projected.

The performance/art installation is an homage to the inherent dignity of manual labor: Alkaid’s immigrant father was a washer/dryer repairman who proudly taught his kids the trade. But it’s also a rumination on the uncomfortable “intersectionality of being an artist with these inherited labor skills,” Alkaid says.

“Hernecia Laboral” is part of Concrete Hope (Esperanza Concreta), a major exhibition coming this fall to SMC’s Pete and Susan Barrett Art Gallery. Presented by award-winning curator and SMC Art History of Photography instructor Erika Hirugami, the exhibition shines a spotlight on 38 emergent Latine/x photographers and lens-based artists across Southern California.

“We’re coming together to celebrate latinidad at a time when the political climate is turning against us,” says Erika, the show’s curatorial director, referring to the federal government’s attack on immigration.

*

The Barrett’s Concrete Hope is the epicenter in a constellation of more than 20 related exhibitions across Los Angeles, San Bernardino, Riverside, San Diego, and Orange counties. Designed by a curatorial team led by Erika, these related exhibitions elaborate on the practices of the same artists through solo, two-person, thematic or geographical exhibitions spread across more than a dozen community college galleries and public art spaces.

Collectively, the ambitious yearlong project is titled FotoSoCal.

Its roster of featured artists came together organically, starting with a handful of Erika’s colleagues from Claremont Graduate University (CGU). It rapidly snowballed to form “a really beautiful community of Southern California photographers who all know each other, stand up for each other, and push each other to do better and thrive.”

Erika now regards all these artists as friends. “We’re all so interrelated, like a big family,” she says.

The driving spirit behind Concrete Hope and FotoSoCal is an unapologetic celebration of the region’s “brown community.” Replete with piñatas, abuelitas, cholos, tatuajes, virgencitas, mercados, rosarios, familia y fotografías, the project embraces latinidad in all its splendid complexity. That includes the lived experiences of Mexican Irish, Afro-Mexicana, Mexipino (Mexican-Filipino), and Jaxicans (Japanese-Mexican). The latter happens to be Erika’s ethnorace.

*

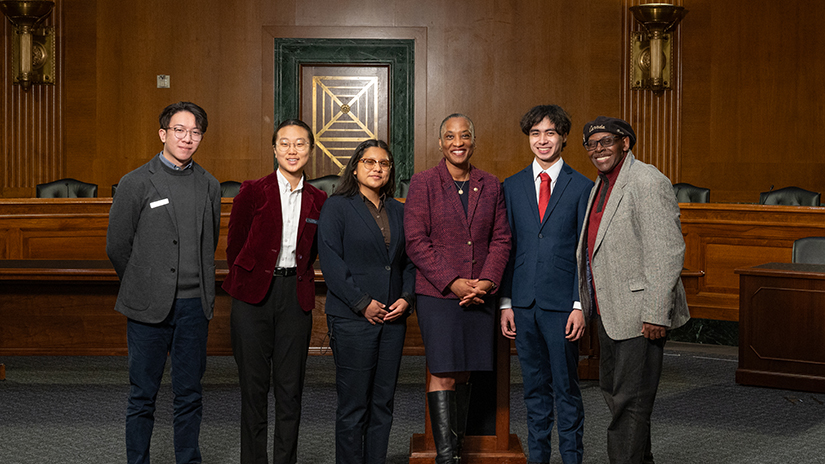

A transnational immigrant born in Guadalajara, Erika traveled between the United States and México more than 30 times before the age of 17. Formerly undocumented, of Otomí and P’urhépecha lineage, she has various levels of proficiency in four languages, including Nahuatl.

Her formal education is rooted in community college, having spent six years earning “an assortment of AA degrees” at Los Angeles Valley College before completing bachelor’s degrees in art history, Chicano/a, and Mexican studies at UCLA and a master’s in art business at CGU. She is currently a PhD candidate at UCLA, where she recently received two master’s degrees in aesthetic theory. Her scholarship focuses on “undocreatives,” artists in the undoc+ spectrum” (formerly or currently undocumented). She’s writing her dissertation, titled “Braiding the Aesthetics of Undocumentedness,” and expects to enter the academic job market next year.

As an independent curator, Erika is the founder of CuratorLove and co-founder, with University of Virginia art professor Federico Cuatlacuatl, of the UNDOC+Collective, which champions undocreatives working in the contemporary arts ecosystem.

Alongside her scholarly and curatorial responsibilities, Erika teaches history of photography at SMC and Cypress College, exhibition design at Mission College, and immigration policy and politics through contemporary art at UCLA. She plans to integrate both Concrete Hope and FotoSoCal into her curricula.

Passionate about her role as an educator, Erika sees her students as “these wonderful individuals who will probably change the world—not that they know it yet.”

She regularly invites them to exhibitions and creative programming all over the region, “and it totally warms my heart when they follow through,” she says. “They’re so eager not just to learn, but to be involved in the community of photography.”

*

With Concrete Hope running at SMC’s Barrett Gallery from September through May 2026, SMC students won’t need to go far to be involved.

According to SMC Art Department Chair Walter Meyer, this exhibition demonstrates the Barrett’s commitment to creating necessary campus conversations around social justice and equity.

“Barrett Gallery Director Emily Silver has really moved the needle on centering social justice, campus-wide engagement and community outreach as the foundation of the Barrett’s programming,” he says. “This groundbreaking exhibition is an exemplar in this trajectory. Emily’s vision, combined with Erika’s urgent and timely project, marks yet another step towards transforming the SMC Art Department and the Barrett Gallery, in our quest to shine as a beacon of social justice, embodied in the arts.”

Nine months is a long run for an art exhibition, but Erika promises no two visits to the Barrett will be the same. She has peppered artist-led gallery encounters and performance pieces throughout the academic year.

The more than 70 artworks that make up Concrete Hope defy the conventions of photography-based exhibitions, which Erika considers “so boring.” Instead of uniform rows of two-dimensional prints on the wall, she promises “all kinds of mixed-media. Concrete Hope includes art that will hang from the ceiling, be made of volcanic rock, light boxes, cinder blocks and propane tanks.” Not to mention a washing machine.

The Concrete Hope exhibition catalogue, too, will be boldly experimental. In a departure from museological convention, the artists themselves will contribute to the conversation with one another—“which is peculiar and also magical,” Erika says. “There’s rarely scholarship from the artist’s perspective. Here they’ll be exploring their friends’ photographic practices.”

Erika’s curatorial statement likewise defies norms. It whimsically titles sections to connect specific artworks with popular songs that inspired them—“so technically speaking, you can dance to my curatorial statement,” Erika says, smiling.

But on another level, Concrete Hope is deeply serious. The title of the Barrett Gallery exhibition refers to a form of hope not grounded in far-off dreams but in action. The concept was articulated by Cuban-American visual theorist José Esteban Muñoz.

When Erika embarked on this exhibition project two years ago, she had intended to challenge the “contemporary art ecosystem of Los Angeles that doesn’t serve Latinx emergent photographers.” So-called “brown museums” heavily prioritize muralism, painting, and works on paper. “Photography is like the bastard child that gets pushed far away,” Erika says. Meanwhile, museum spaces that focus on lens-based art tend to showcase artists from Latin America, not homegrown Latinx photographers.

Because of the current political climate, daily ICE raids and mass deportations lacking due process, FotoSoCal has acquired new urgency.

Responding to the philosophical writings of Muñoz, Erika thus takes “actionable steps.”

“Under the current administration,” she says, “my community is being targeted violently, aesthetically, and politically. This project aesthetically visibilizes the opposite. I’m here to unapologetically celebrate my community, and I truly believe these photographic works have the power to shift the narrative.”

* * *

More information on the exhibit:

Concrete Hope has its soft opening on September 23. A series of lectures leads up to the official October 14 kickoff event, featuring a campus-wide symposium and opening reception at the Barrett.

Also curated by Erika are two exhibitions at sister SMC venues. Whittier-based photographer and instructional assistant at Cypress College Juan Manuel Valenzuela’s solo exhibition, titled “Nurturing Masculinities,” opens September 18 and runs through Nov 7 at SMC’s Emeritus Gallery. SMC’s Malibu Campus Gallery will join FotoSocal in March 2026.

Artist keynotes are scheduled through the fall semester, starting with Alkaid Ramirez and Felix Quintana at the Barrett on October 15, and Aydinaneth Ortiz and William Camargo in the Arts Complex on November 6. The Spring 2026 semester will feature a film festival and symposium in February, and a book launch in May

* *